Close at hand

On September 9, 2014, Tim Cook stood on stage at the Flint Center in Cupertino, California and gestured to a giant screen. The lights dimmed; Cook sidled offstage. The film introducing the Apple Watch began. Jony Ive’s voice boomed gently through the sound system: “You know it’s driven Apple from the beginning this compulsion to take incredibly powerful technology and make it accessible, relevant and ultimately personal.” The Apple Watch wouldn’t be cold or distant — not the kind of thing you’d want to store at arm’s length, “on your desk or in your pocket.” The Apple Watch would be cherished. Intimate. Worn.

If intimacy was at the heart of the Apple Watch project, history was conceived as its spine. In an April 2015 feature for Wired — titled, perhaps not coincidentally, “The Secret History of the Apple Watch” — journalist David Pierce shared a glimpse of the device’s origins. At the project’s inception, according to Pierce, Ive “began a deep investigation of horology, studying how reading the position of the sun evolved into clocks, which evolved into watches. Horology became an obsession. That obsession became a product.” Alan Dye, Apple’s VP of User Interface Design, recounted that “There was a sense that technology was going to move onto the body…We felt like the natural place, the place that had historical relevance and significance, was the wrist.” Together, the executives drew a line from the sun to the wrist.History pointed to a tool they’d designed.

A closer look at history points somewhere else — somewhere technology has always been. At our fingertips; attached to our hips. In our pockets.

Portability & pageantry

The earliest pockets were pouches worn on belts. This practice dates back to the Bronze Age, at least. Ötzi the Iceman, “Europe’s oldest known natural human mummy,” died around 3200 BCE with a leather pouch slung around his waist. Ötzi “used his belt pouch to store various flint tools: a scraper, a drill and a flint flake,” as well as a “7.1 cm bone awl…[which] could be used for various jobs from sewing to tattooing, or simply as a toothpick,” all stashed within a tangle of tinder fungus. These weren’t the only tools Ötzi carried, but they were the ones he kept closest at hand.

In the Postclassical Era (200 CE–1500 CE, at the outside), the belt practice held. Medieval men and women alike wore girdles to cinch their tunics and dresses at the waist. From their girdles, they hung keys, knives, combs, wallets, and even — between the 13th and 16th centuries — books.

15th-century girdle book from Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0. My thanks to Jennifer Brook for pointing me in the direction of girdle books.

Girdle books were designed for both portability and pageantry. In a paper presented at the St. Louis Conference on the Study of Manuscripts in 2011, Margit Smith writes:

The girdle book has the advantage that it can be read without being detached from the belt, as it hangs upside down in its normal state; when swung up to be read, however, the text faces in the correct direction. After reading, it could just be dropped and was again at hand the next time it was needed making it especially convenient for monks, priests, and clerics who traveled through the countryside for church services in monasteries and convents.

The essential convenience of girdle books extended beyond enabling mobility to underwriting frequency:

To nuns, obliged to say required prayers throughout the day, at work or at rest, they were immediately accessible.

Yet convenience wasn’t the only reason to wear a book around one’s waist; in Smith’s words, “the girdle book was not only functional.” A 2005 summary of her research, co-authored with Jim Bloxam of Cambridge University, observes that girdle books “were used symbolically to denote knowledge, wealth, intellectual curiosity and learning.” Although girdle books were “prized for their contents,” it was also undeniable that “their sumptuousness provided a ready indicator of their owners’ status in life.”

Girdle books could serve as status symbols because their owners proudly displayed them for all to see. Attached to their garments, girdle books represented an extension of medieval identities. But waist-hung belongings weren’t always visible. What went inside and what went out depended on how society weighed status against safety.

Inside & out

Until about 1250 CE in Medieval England, men typically hung their purses outside their tunics. Midway through the century, fashions changed; wallets and purses started to be “placed under the tunic, out of sight.” It was around this time, too, that fitchets emerged; “resembling modern day pockets,” these slits cut into tunics afforded access to the pouches or keys hung underneath. It seems likely that the inward shift was an attempt to thwart cutpurses, precursors to pickpockets; it’s harder to cut and run with something hidden under folds of cloth.

Nuremberg woman in house dress, Albrecht Dürer, circa 1500–1501. Public domain.

Women, on the other hand, still regularly hung their purses outside their garments through the turn of the 16th century, as depicted in the portrait above. In England, this changed starting around 1550 with the onset of the Elizabethan era. According to one history of handbags,

During the Elizabethan era, women’s skirts expanded to enormous proportions. Consequently, small medieval girdle purses were easily lost in the large amounts of fabric. Rather than wear girdle pouches outside on their belt, women began to wear their pouches under their skirt.

By 1760, pockets were “usually worn underneath [women’s] petticoats,” accessed through slits in the outer and inner layers. James Dalton, a “notorious thief,” counseled women against this habit as he stood trial in early-18th-century London; “what gave [thieves] the greatest advantage, was the custom the women have of wearing their pockets under their hoop petticoats, where they might whip hold of it without the least interruption.” On the other hand, “if to the contrary they would put their pockets between their hoops and their upper petticoats, they might defy” all who pursued them.

Meanwhile, in 17th-century Japan, men accommodated the absence of pockets on their kimonos by dangling small containers from their sashes:

Because traditional Japanese garb lacked pockets, objects were often carried by hanging them from the obi, or sash, in containers known as sagemono (a Japanese generic term for a hanging object attached to a sash). Most sagemono were created for specialized contents, such as tobacco, pipes, writing brush and ink, but the type known as inrō was suitable for carrying anything small.

Inrō-netsuke pairing via Wikipedia. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 FR.

Sagemono hung on the outside of kimonos, and could therefore be conscripted into serving a secondary, subversive aim of status signaling:

Originally worn as part of a male kimono ensemble by men of the warrior class, inrô and netsuke [carved counterweights] developed as a form of conspicuous consumption within a culture that imposed a rigid four-tiered social system with warriors at the top, followed by farmers who tilled the land, artisans who crafted material goods, and merchants at the bottom.…Given that the merchants were economically better off than many members of the socially superior military class, inrô and netsuke allowed merchants to display their wealth without breaking any sumptuary laws that regulated the types of houses they could build or fabrics they could wear.

Sagemono dangled not only in plain sight, but outside the protocols that governed daily life. Through their fundamental functionality, these containers enabled men to confound societal compartmentalization.

Seams & silhouettes

Sewn into the seams of men’s breeches starting sometime between the late 17th and early 18th centuries, integral pockets represented a functional step forward. Women’s clothing, however, went a different direction.

As the 18th century gave way to the 19th, “[i]nner-clothing storage space” for women “gave way to the external ‘reticule,’ considered a precursor to the modern handbag. They were carried on arms or in hands, and they held just about nothing.…In terms of functionality, it was a major downgrade.” Chatelaines, a kind of waist-hung decorative metal toolkit, surged in popularity as a counterweight.

“Chatelaine with seals (mid-late 18th century)”, by aehdeschaine on Flickr. Taken at the British Museum. Licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0.

In the preface to an in-depth interview with chatelaine expert Genevieve Cummins for Collectors Weekly, Hunter Oatman-Stanford describes the range of possibilities chatelaines represented:

Like a customized Swiss Army knife, a chatelaine provided its wearer with exactly the tools she needed closest at hand. For an avid seamstress, that might include a needle case, thimble, and tape measure, while for an active nurse it might mean a thermometer and safety pins.

Chatelaines sidestepped the tyranny of the reticule, but the tension between function and fashion remained. The devices were made by jewelers and, in some contexts, considered beautiful; according to Cummins, “on these long, flowing gowns a chatelaine broke the plainness of a skirt.” But the most useful chatelaines — the ones designed to facilitate sewing, nursing, or painting — “you would’ve only worn around the house.”

Whereas in earlier centuries the tension between wearing waist-hung tools inside or outside of one’s garments came down to safety vs. status, in the 18th and 19th centuries, women’s silhouettes became the major concern — and have remained so since. In a 2011 piece for the Spectator, Paul Johnson cites an academic article by C.T. Matthews titled “Form and Deformity: The Trouble With Victorian Pockets,” which explores the social context that made internal pockets unthinkable for women. Paraphrasing Matthews, Johnson writes:

It was argued that [women] had four external bulges already — two breasts and two hips — and a money pocket inside their dress would make an ungainly fifth.

“People on Alexanderplatz III,” by Sascha Kollmann on Flickr. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Fast forward to the 21st century and the story hasn’t changed much. Camilla Olson, “creative director of an eponymous high tech fashion firm,” spoke to The Atlantic in September 2014 on exactly that topic for an article on “The Gender Politics of Pockets”:

Women’s pockets are often located near the hip area, where many women would prefer not to attract attention. For that problem, Olson thinks a holster-type of product would work best — a compromise between having a purse and placing an unsightly bulge around what is culturally perceived in the West as a “problem area.”

“It’s got to be an accessories solution,” she theorized. “Chanel just came out with a holster type of thing that is really, really pretty. Or a fanny pack that was stylish. Or a shape to wear about [the body].”

About the body, but not against the body. Throughout the centuries, the verdict for women has been clear: bonus bulges must be clearly delineated. Body, tool; dress, chatelaine; jeans, holster; blouse, handbag. Anything to keep the underlying silhouette clean.

Proximity & persuasion

In a very real way, what people tuck into their pockets signals what they care about. Ötzi the Iceman carried fungus to make fire. Japanese men in the Edo period carried medicine and seals. Queen Elizabeth I carried a miniature jewel-encrusted devotional book. European women in the 18th century carried money, jewelry, personal grooming implements, and even food. Here in 2015, we carry cellphones — never letting them out of our sight.

Drawing of a pocket watch movement from an 1891 encyclopedia, via Wikipedia. Public domain.

If what we put in our pockets is important, to advertise a product as pocketable is to imply that it’s indispensable: something you’ll always want by your side. Pocket watch manufacturers adopted this approach early; purveyors of pocket knives, pocket handkerchiefs, and pocket books (also known as paperbacks) followed suit. Technologies all, these tools still seem primitive relative to slim electronic bricks we haul around today. To find a direct ancestor of the cellphone, we need only look back as far as 1970: the year the pocket calculator was born.

Canon Pocketronic, posted to Flickr by Jason Carter. Licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

In reality, the first “pocket calculator” wasn’t. Although advertised as being “So small, it fits in your pocket,” it would have been more accurate to say it was small enough to hold in your hand. Optimistic advertising aside, as the first handheld, battery-powered calculator put into production, the introduction of the Canon Pocketronic still constituted a milestone.

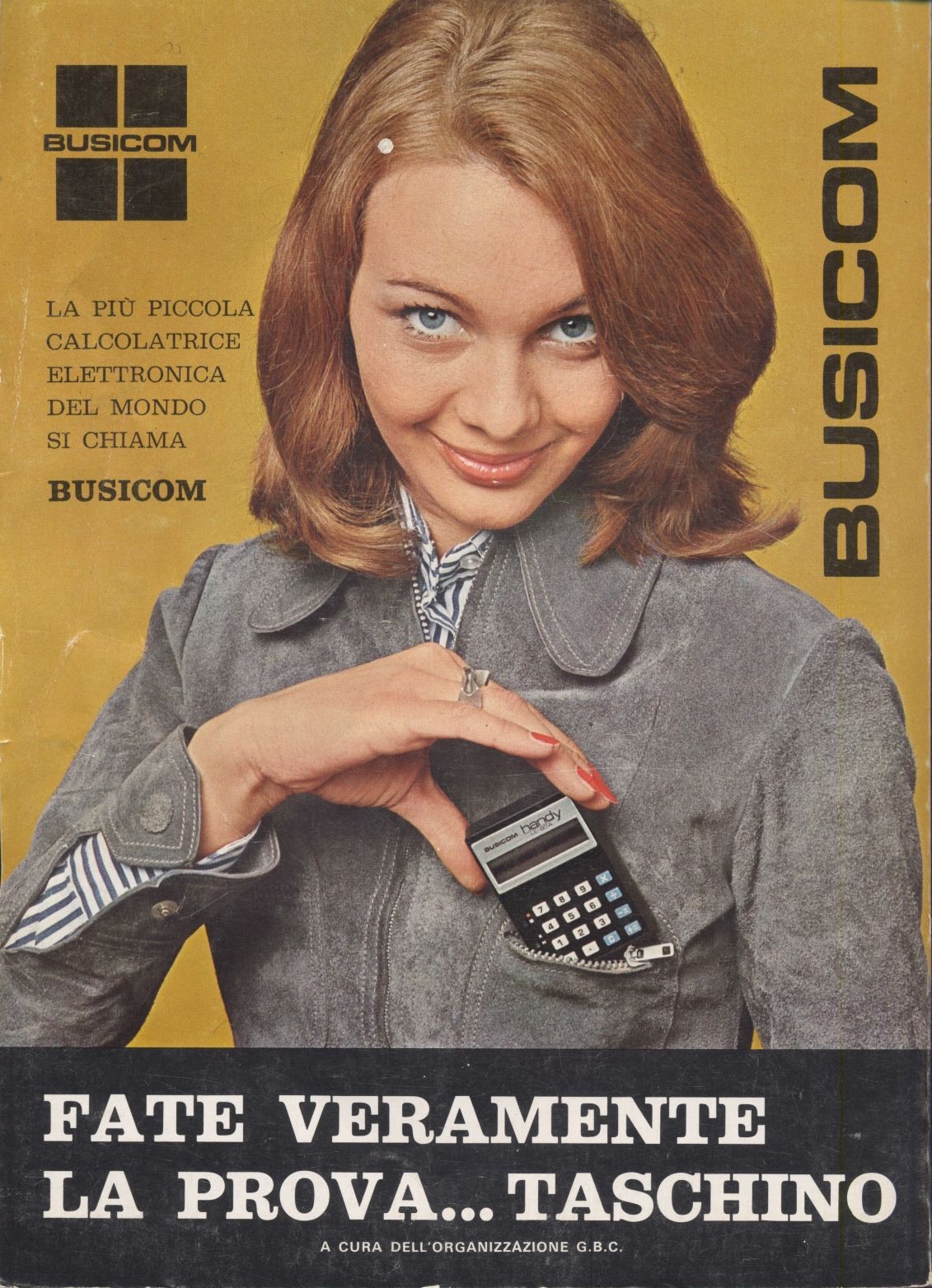

A year later, in 1971, Busicom came out with the first true pocket calculator: the Busicom LE-120A HANDY LE. According to the Vintage Calculators Web Museum, the HANDY LE was “the first calculator small enough to be truly described as ‘pocket-sized’, the first calculator using an LED display (12-digits), and the first hand-held calculator using a ‘calculator on a chip’ integrated circuit.”

Early 1970's Italian calculator advert, posted to Flickr by Matthew Rutledge.

The one-two punch of the Pocketronic followed by the HANDY LE illustrates an inescapable duality: it’s impossible to talk about pockets without also talking about hands. Handkerchiefs and handbooks belong in pockets as surely as pocket calculators come in handy. The history of pockets is the history of handheld technology; the history of handheld technology is the history of how people have remade the world.

And so it was that in 2001, Apple could introduce the device that would change the music industry forever with a simple tagline: “Ultra-Portable MP3 Music Player Puts 1,000 Songs in Your Pocket.” At the keynote announcement, Steve Jobs put the iPod’s pocketability front and center:

The coolest thing about iPod is, the whole — your entire music library fits in your pocket. You can take your whole music library with you, right in your pocket.…You can take iPod bicycling, mountain climbing, jogging, you name it, and you’re not going to skip a beat.

A few minutes later, Jobs reached the big reveal:

I happen to have one right here in my pocket.

With that, Jobs lifted the iPod out of the front pocket of his blue jeans and held it high for the audience. The rest is history.

Pockets matter because they’re personal. What we wear at our waists is at least as intimate as what we wear on our wrists, and what we’ve worn there over the centuries tells us a lot about who we are, how we’ve changed, and how we’ve stayed the same. We’re greedy; we’re vain; we’re hungry; we’re late. We want to start fires and listen to a thousand songs.