The Aesthetics of Generative Models

Prompt: “giant blue and orange marble run as big as a mansion,” generated in Midjourney. I used “blue and and orange” explicitly early in my prompting journey before realizing that Midjourney effectively defaults to blue and orange.

The shock of generative models is how good their output can be. If you’ve played with an image generation model such as Stable Diffusion, Midjourney, or DALL·E recently, you may have experienced some of that shock. First, you submit a prompt and wait a few heartbeats in anticipation. In Midjourney, you can even watch as the image resolves from fuzzy to crystal clear—as though you’re an analog photographer in a darkroom, waiting under dim red lights for your picture to develop. Then, a set of images materializes. Within the set, there’s variation in the details but consistency at a qualitative level: the images are, on average, surprising. Sometimes they’re not at all what you had in mind, but that’s not always a negative; sometimes they’re better than what you had in mind. And even when they’re “off,” they’re not bad. They’re something else. They have potential.

Good, bad, better—these are aesthetic judgments we’re leveling on the output of generative models. The statements feel true enough that we toss them off casually, but then the moment you turn around and interrogate them—What is “good”? What is “bad”? What is “better”?—the conversation can get philosophical quickly. In fact, aesthetics is an entire branch of philosophy, one seemingly tailor-made for the study of generative models. From Wikipedia:

Aesthetics, or esthetics, is a branch of philosophy that deals with the nature of beauty and taste, as well as the philosophy of art (its own area of philosophy that comes out of aesthetics). It examines aesthetic values, often expressed through judgments of taste.

Aesthetics covers both natural and artificial sources of experiences and how we form a judgment about those sources. It considers what happens in our minds when we engage with objects or environments such as viewing visual art, listening to music, reading poetry, experiencing a play, watching a fashion show, movie, sports or even exploring various aspects of nature. The philosophy of art specifically studies how artists imagine, create, and perform works of art, as well as how people use, enjoy, and criticize art. Aesthetics considers why people like some works of art and not others, as well as how art can affect moods or even our beliefs. Both aesthetics and the philosophy of art ask questions like “What is art?,” “What is a work of art?,” and “What makes good art?”

I am not a philosopher, but I am a forever student. Down the rabbit hole of exploring the ways generative models enable tools for imagination, I noticed that the way was smoother whenever I was in an aesthetic groove, and choppier whenever I wasn’t. This got me thinking about how “aesthetic”—in the plainspoken, everyday sense—relates to generative models and what we expect of them. The philosophical connection, once I made it, felt like both a bonus and a liability. A bonus because it meant there was so much to explore; a liability because there was already plenty to explore in the realm of generative models. Were aesthetics a distraction, or the key to the whole thing? I decided to give myself the space of this essay to feel my way through.

The Front Door

As you walk down any street, every front door has something to say. Color, shape, windows or no; the typeface of the building number beside it. Within a built environment, it’s safe to assume someone chose every visible element, and likely paid extra attention to what you saw first. What’s on the outside sets our expectations about what we’ll find on the inside.

For each generative model, there exists a webpage that effectively serves as a front door. That web page sets expectations about what each model is capable of—and, on another level, what it’s “for.” That last elision is a tricky one, because the image generation models of today are still showcasing their virtuosity; as one of my favorite thinkers Robin Sloan observes in his piece “Notes on a Genre,” the present genre of AI artists is “I see what you did there.” But the images used to highlight virtuosity ironically exist within a limited range, at least as conceived today. The true virtuosity of these models lies in their wild potential: that they can surprise even their makers; that it sometimes seems they can do almost anything. Yet what is shown up front is a radical subset of what’s possible…with an odd symmetry across the models in what’s showcased.

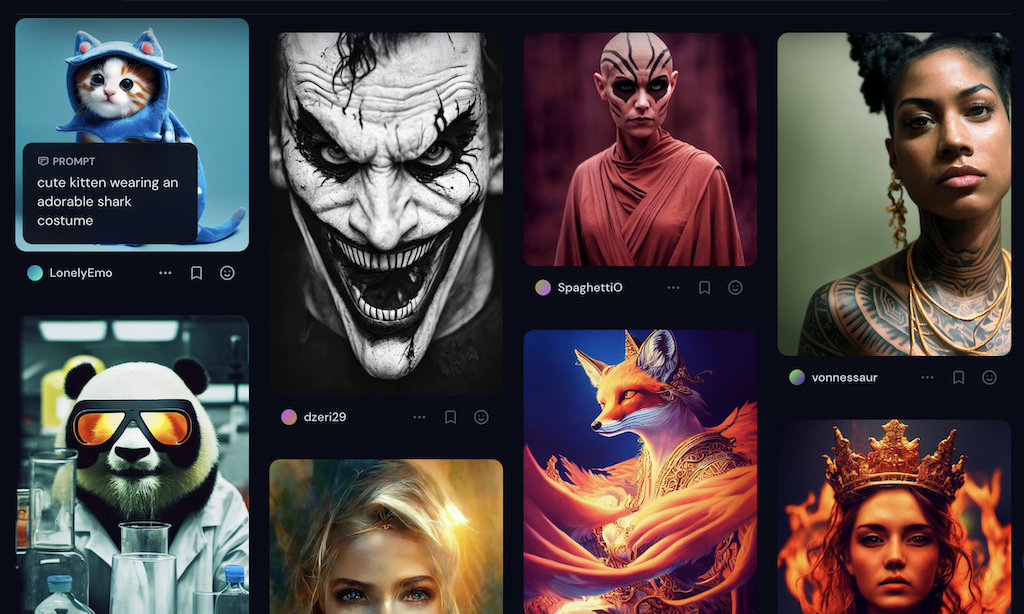

The sample images that currently light the way for image generation models anchor on whimsy, vibrancy, and genre. The sample images curated by OpenAI staff for DALL·E (showcased in empty states throughout the experience) and the Midjourney community gallery represent two takes on what I consider the same aesthetic profile.

Whimsy: In DALL·E’s stable set of curated sample images, the “cute tropical fish” and now-famous “armchair in the shape of an avocado” take playful, childlike topics and textures and render them vividly. In Midjourney, members of the community continuously vote up favorites across channels, so the set is always shifting—but from my exposure, the screenshot above is representative. “Cute kitten wearing an adorable shark costume” and “Portrait of a panda mad scientist mixing potions in a lab wearing cool safety glasses” both capture the playfulness of creatures doing absurdist things in a hyperrealistic way, highlighting each model’s capabilities.

Vibrancy: Saturated color schemes are common to both DALL·E and Midjourney’s featured images. DALL·E’s curated images strike me as more rainbow-bright (the purple of “A photo of a white fur monster standing in a purple room”; the rich greens of the avocado chair), where Midjourney’s model is known for featuring orange and blue more prominently—a cinematic callback (whether intentional or emergent) in its own right. With both models, the highlighted images are high-contrast and seem to leap off the screen.

Genre: Science fiction is a popular theme in both DALL·E’s and Midjourney’s sample sets, and Pixar-style cute animals are popular subjects in both. Fantasy, superheroes, and conventionally pretty women in scifi / fantasy / superhero contexts are overwhelmingly popular in community-powered Midjourney. “Astronaut,” “desert,” “robot,” “monster,” “nebula,” “cyborg,” “future,” and “flying cars” are just a few of the prompt words featured in DALL·E’s curated sample set. In that one moment-in-time screenshot of Midjourney’s community gallery alone, we see a character from the Star Wars universe (Asajj Ventress), a character from Batman (the Joker), and a very Game of Thrones-looking queen character bathed in fiery red.

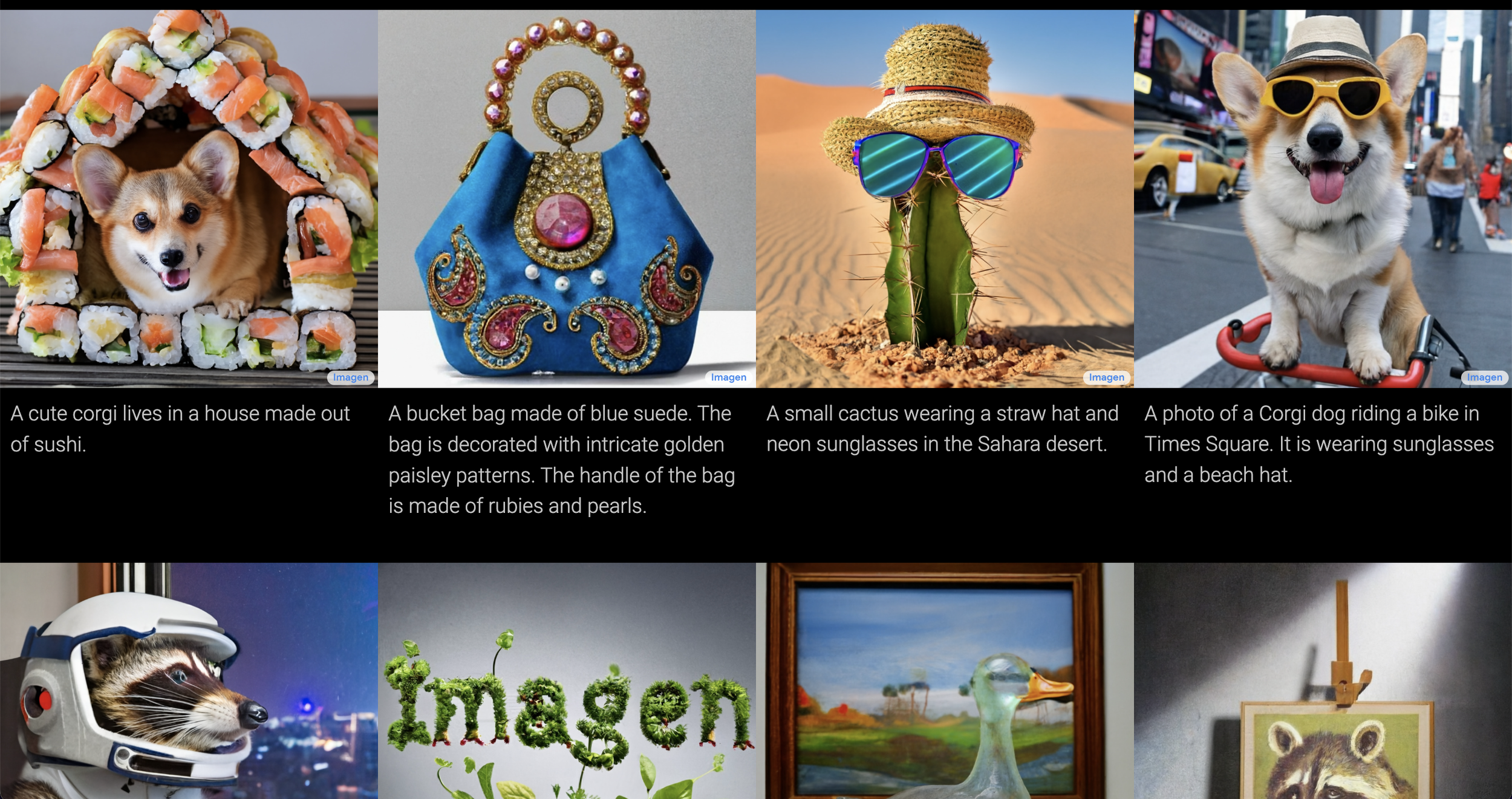

It’s not just about Midjourney or DALL·E, though; the same patterns show up in the sample images for Google’s model, Imagen, and Stable Diffusion.

My assumption is that the images showcased for each model reflect a blend of intentionality and coincidence. Intentionality: show how powerful the models are at generating detail and vivid variety; lean on whimsy to showcase non-threatening use cases. Coincidence: it would not be a huge stretch to say that the engineers who have devoted their careers to building futuristic technology (in DALL·E’s case) or the savvy early adopters who take models for a whirl (in Midjourney’s case) often like science fiction, anime, and fantasy—and reach readily for that library of tropes when faced with a blinking cursor. Yet whether intentional, coincidental, or a blend of both, the effect is the same: if you glimpse one of these models’ front doors without expectations about “what it’s good for” and what they’re capable of, you will come away with the distinct impression that they’re for whimsy and genre, vibrantly rendered. And if that’s not your style, it’s easy to think that these engines aren’t for you. You walk up to the front door to knock, but then hesitate with your hand held high—do you even want to go in?

The Entryway

Past the front door of most buildings, you’ll find an entryway—a space of transition. In a home, you might see a coat rack; a closet; a place to take off your shoes and settle in. With image generation models, once you make it past the front door of showcased images and into an interactive experience of being able to engage with it directly, there are still props all around to help you get situated. Those props have something to say about aesthetics, too.

In DALL·E, the “Surprise me” button automatically fills the prompt field with a text string representing a prompt for one of the sample images shown on the way in. “3D render of a cute tropical fish in an aquarium on a dark blue background, digital art”; “an oil painting by Matisse of a humanoid robot playing chess.”

The prompt field in the interface to DALL·E, filled with sample prompt text by selecting “Surprise me.”

Since Discord is the interface to Midjourney, its entryway is more like the great hall at Grand Central Station; there’s all the clamor and echo of other people chatting, prompting, and learning out loud. The #getting-started channel points to a quick start guide that in turn points to a resources page with a link to their official guide to prompting. The guide to prompting is poetic in its own right; evocative headers include “Anything left unsaid may surprise you” and “Speak in positives. Avoid negatives.” Even though the guide offers instructions to finding your own way through Midjourney, the examples offered still align to the default aesthetic seen in the community gallery. For the instruction “Try taking two well defined concepts and combining them in ways no one has seen before,” the examples offered are “cyberpunk shinto priest” “psychedelic astronaut crew” “river of dreams” “temple of stars” “queen of time” “necromancer capitalist.” For “Try visually well-defined objects,” the examples are “Wizard, priest, angel, emperor, necromancer, rockstar, city, queen, Zeus, house, temple, farm, car, landscape, mountain, river.”

Every model has its own ornate entryway; this section could go on and on. What’s most interesting to me about Midjourney specifically, though, is that the model’s default aesthetic is barely recognizable as a traditional genre; it’s something all its own, a hodgepodge that I personally respond to much more strongly than I do to the images featured in any of the showcased samples from any model. David Holz, the founder of Midjourney, tried to describe it in an interview with The Verge:

I think the style would be a bit whimsical and abstract and weird, and it tends to blend things in ways you might not ask, in ways that are surprising and beautiful. It tends to use a lot of blues and oranges. It has some favorite colors and some favorite faces. If you give it a really vague instruction, it has to go to its favorites.

This has certainly been my experience. It seems that whatever tuning has taken place in Midjourney strongly favors blue and orange and has a bit more “personality” than what I get out of DALL·E. For instance, one of my early Midjourney prompts was “beautiful gradient,” which returned a tidy grid of four images that were all blue and orange, and all of a piece.

Prompt: “beautiful gradient,” generated in Midjourney

It so happens that Midjourney’s favorites are also more aligned to my personal taste. This was the aesthetic groove I had been waiting for without realizing it, and where things started to get really interesting for me.

The Inner Chamber

Past the entryway, down a hallway and a staircase or two, you finally make it to the inner chamber. You can set down your bag, gaze around, let down your guard: settle in for a while. In the inner chamber, you are a guest—but you can still make yourself at home.

What it took to find my aesthetic groove within these image generation models was, first, feeling motivated to even try. The moment that tipped me over into motivation wasn’t anything to do with work; it was a moment of aesthetic response. For many years, I’ve responded positively to the aesthetic of Wes Anderson’s movies. I haven’t even seen all of Wes Anderson’s movies, so it’s not about that; it’s about muted pastels and offbeat sincerity. One day, while scrolling a social feed, a set of images for an imagined moodboard for a “Wes Anderson fashion show,” generated in Midjourney, caught my eye and gave me pause. I liked them so much! And if those were possible, what else was possible? Hope gave me the energy to try. From there, I set about this deep dive in earnest. Even after over a year of being intellectually engaged with generative models, it took aesthetic enchantment (and, access; I only recently got into DALL·E, and Midjourney only opened up to the general public a few weeks ago, at the start of August 2022) to send me down the rabbit hole for real.

The next ingredient in finding my aesthetic was to clear the slate. I went inside my own imagination and used freewriting as a springboard for organic prompts, trying them in both DALL·E and Midjourney in most cases. I had to spend time with my own blank page and blinking cursor absent the influence of themed channels in Midjourney’s Discord interface, or the sample images set as loading indicators and educational reminders in DALL·E, to even remember how to put words to what I like. The more keywords I tried, the more excited I got: the outputs could be so personalized. After one particular breakthrough, I typed in my notes “I reacted much, much more positively to the model output once it was in a nameable style that I personally like—blueprint and/or 1930s print ephemera.…I think everyone should have to generate images in a style they personally like before giving up on image generation. Looking at other people’s images is like looking into other people’s subconsciouses—a little unseemly.”

Within abundance, it takes curation to shape our sense of what’s possible. There is opportunity for tools for imagination that help users iteratively identify an aesthetic they like, then lock that aesthetic along various dimensions (for instance, color palette or illustration style) and vary it in others. In the meantime, it takes a certain relentlessness to block out the noise of the defaults and find your own way.

Windows

A front door is chosen, and mostly opaque. It sets the tone, but it can quickly get out of date, go out of style; repainting it is an effort. Meanwhile, inside a building’s walls, life unfolds. Through the windows, when the curtains are open, it’s possible to glimpse more of the clamor of what’s really going on.

There are many windows into the world of generative models. Twitter is one big bank of windows; whenever I find a new AI artist posting images I feel an aesthetic response to, my heart leaps. Midjourney’s Discord is another; all prompts and their output are public unless you pay extra to keep them private. Stable Diffusion will be interesting, since it can run locally on users’ computers; the output there will be hidden from view until specifically shared, the curtains closed.

It is still surprisingly hard to find the right window if your personal aesthetics veer away from sci-fi / fantasy / anime, but one starting point can be reflecting on the artists you’ve responded to in museums and searching for their name + the name of a model. For instance, just now I searched Google for “agnes martin midjourney” and it took me straight to a tweet by @Yazid which is very me: “A calendar in the style of Agnes Martin.” And now, of course, I’m following Yazid.

The “artist’s name” access point is an interesting one, common across models—recall DALL·E’s sample prompt, “an oil painting by Matisse of a humanoid robot playing chess,” and note the section of the Midjourney prompting guide “Try invoking unique artists to get a unique style.” The prompt guide for Stable Diffusion’s DreamStudio suggests “To make your style more specific, or the image more coherent, you can use artists’ names in your prompt. For instance, if you want a very abstract image, you can add ‘made by Pablo Picasso’ or just simply, ‘Picasso’. Below are lists of artists in different styles that you can use, but I always encourage you to search for different artists as it is a cool way of discovering new art.”

“A cool way of discovering new art.” Discovering new art. Twitter and other channels are powerful windows into the work AI artists are doing with these models, but there’s also a perspective where every image that gets generated is a window onto the model itself–as though all the images are already there. (And in a way they are—in latent space.) It’s search all the way down. The key to the inner chamber is to name what we’re looking for.

Light

Between buildings, if you’re looking for it, you can glimpse the horizon. The sun comes up, then arcs through the day; light is never the same twice. The same reality looks different at dawn than at golden hour than at dusk.

The aesthetics of generative models are slippery. The models can do almost anything, but how do we learn what they can do? By trying, but what gives us the energy to try? What I’ve seen is that aesthetic response is a powerful factor in how people relate to generative models. In the philosophical sense, aesthetics is about “taste”—but taste is not absolute. It’s cultural, it’s personal, it’s relative. It shifts with the light. And taste is something we can explore in much more precision than ever before through the nuanced permutations possible in generative models. When one set of terms is held constant and only the aesthetic terms are varied, we can get close to a complete gradient of possibilities and then ask ourselves: what do we like best? Generative models are capable of creating synthetic data for defining taste.

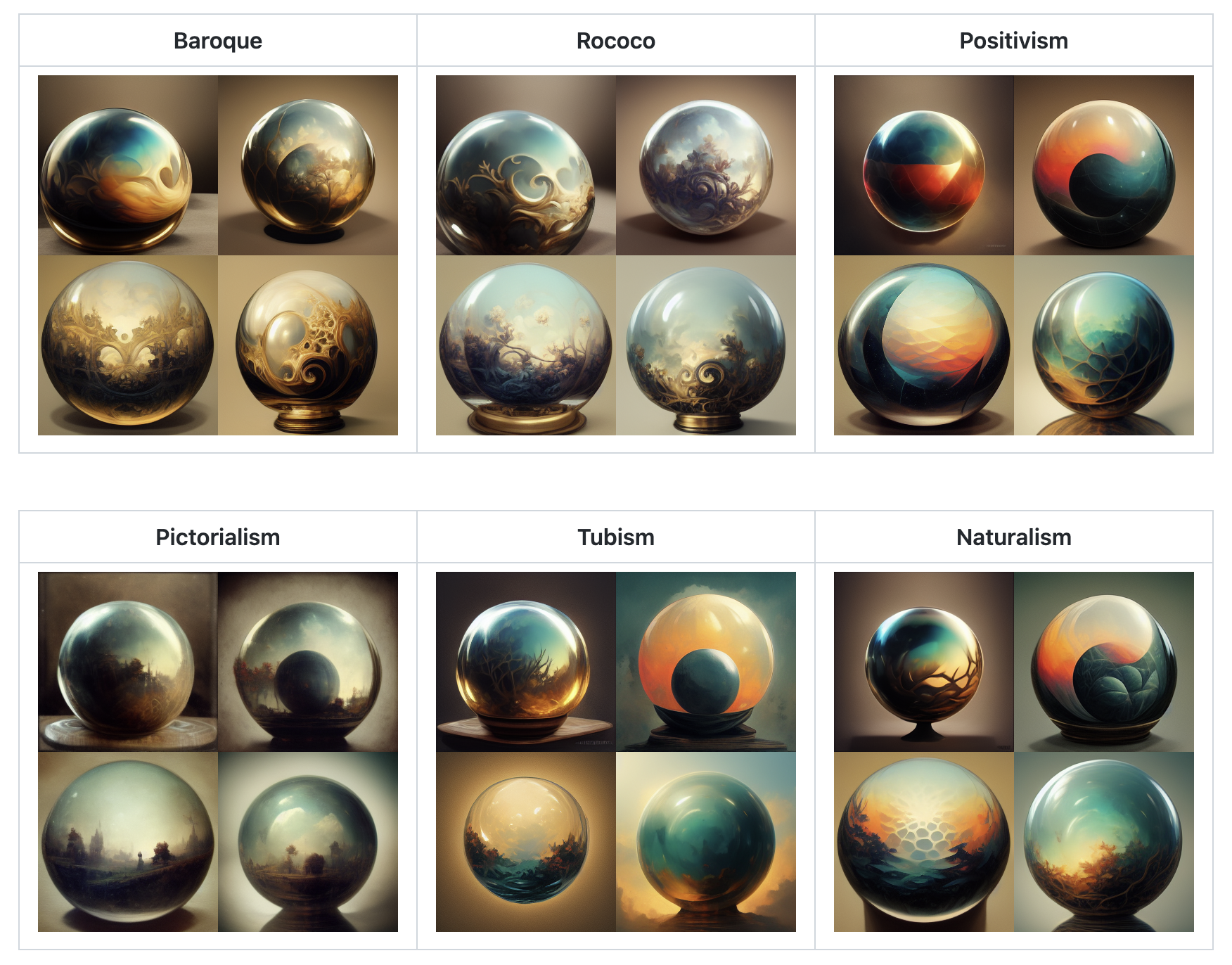

In the unofficial Midjourney styles and keywords reference project on GitHub, style words and other keywords are paired with the word “sphere” in prompts to show clean comparisons of what each style does to a sphere.

And yet…what do we like best? Infinite conjoint analysis is not at the core of aesthetic response. The Wikipedia article on aesthetics notes that the philosopher Daniel Dutton “identified six universal signatures in human aesthetics” (which other philosophers of course contest and complicate), one of which is “special focus”: “Art is set aside from ordinary life and made a dramatic focus of experience.” We can feel in ourselves an aesthetic response to individual outputs of generative models and use that to light the way, but the most novel and dramatic experience available right now is immersing in engaging with the models themselves.

For those who have taken the plunge into the world of generative models, the awe-inspiring overwhelm of immersion is a common response. From Robin Sloan again, on using Jukebox from OpenAI: “Using Jukebox feels like exploring the flooded ruins of a once-great city: exactly that slow, exactly that treacherous, exactly that enticing.” And from David Holz, the founder of Midjourney:

Right now, it feels like the invention of an engine: like, you’re making like a bunch of images every minute, and you’re churning along a road of imagination, and it feels good. But if you take one more step into the future, where instead of making four images at a time, you’re making 1,000 or 10,000, it’s different. And one day, I did that: I made 40,000 pictures in a few minutes, and all of a sudden, I had this huge breadth of nature in front of me — all these different creatures and environments — and it took me four hours just to get through it all, and in that process, I felt like I was drowning. I felt like I was a tiny child, looking into the deep end of a pool, like, knowing I couldn’t swim and having this sense of the depth of the water. And all of sudden, [Midjourney] didn’t feel like an engine but like a torrent of water. And it took me a few weeks to process, and I thought about it and thought about it, and I realized that — you know what? — this is actually water.

Water and light are two elements that flood our every day. It seems likely that soon, AI-generated imagery will flood our every day, too. But before that happens, it’s possible to step into the flood on purpose—to feel it out, to experience its totality. What is “good,” what is “bad,” what is “better”? We are feeling our way through.